Titled Unknown Unknowns. An Introduction to Mysteries, the exhibition is filled with whimsical interpretations of the natural world but fails to address the transformative potential and agency of design.

Held at Milan’s Palazzo dell’Arte since 1933, the Triennale International Exhibition has, much like the Great Exhibitions of the 1800s and World’s Fairs of the 1900s, confronted citizens with technological wonders, consumer novelties and instances of national and corporate industrial prowess. By approaching design and architecture through the exhibition medium, in an institutional setting other than the industry fair or trade event, it has also been the precursor of other periodical events and festivals where the work of designers and architects is displayed as the products of culture.

The Triennale’s 23rd edition, titled Unknown Unknowns. An Introduction to Mysteries, is curated by the astrophysicist and chief diversity officer at the European Space Agency (ESA), Ersilia Vaudo and closes on December 11, 2022. Besides its main exhibition, this Triennale also includes the exhibition The tradition of the new, curated by Marco Sammicheli (director of Italian Design Museum Italiano), which approaches how from 1964 to 1996 a small group of designers and architects in Milan reacted to shifts in Italian society by designing aspirational consumer products and environments. In Mondo Reale, Hervé Chandès, artistic director of the Fondation Cartier for contemporary art, brought to the Triennale’s main floor seventeen contemporary artists that explore the real as a rêverie. The Triennale’s theme was also approached in twenty-three remarkably diverse “national pavilions”. Other shows and projects, such as Francis Kéré’s large-scale installations, an exhibition on the experimental calculation machines designed by Ettore Sottsass in the 1970s, a film on Andrea Branzi and the second volume of the Triennale’s video game collection complete an ambitious, six-month events program.

In the Triennale’s thematic exhibition, Vaudo invites visitors to discover the mysteries of the unknown, from human consciousness to antimatter, through interdisciplinary cross-pollinations manifest in over one hundred works by artists, researchers, architects and designers. Such celebration of research is welcome, yet this exhibition overlooks both the complexity and consequence of design as a territory of practice, an established field of knowledge and, indeed, a culture.

Many of the works on show employ the functions and processes of design, such as observing, collecting and interpreting data into actionable information. However, artefacts such as the watercolors André des Gachons painted of the sky over his village between 1913 and 1951 while serving as a volunteer observer of the French Bureau Central de Météorologie, or artworks such as Alicjia Kwade’s 2021 Selbstporträt, a self-portrait as a circle of twenty-four glass vials containing her body’s chemical elements, speak less of the process, conditions and intentions inherent to design practice than of the individual obsessions of their creators. These and other whimsical art-about-science interpretations of natural phenomena—from gravity to math, ants to dust—make up a large part of this curiosity cabinet of charismatic objects, where effect trumps purpose. That is the case of Amy Karle’s 2016 Regenerative Reliquary, a 3D-printed sculpture of a human hand skeleton installed in a bioreactor, or Ani Liu’s 2017 Olfactory Time Capsule for Earthly Memories, a set of earthy scents encapsulated in long-releasing polymers. But especially Antonio Fiorentino’s 2014 Dominium Melancholiae, a glass tank in which a sheet of zinc, the size of Albrecht Dürer’s 1514 Melancholia I engraving, slowly dissolves in a chemical reagent solution. In its caption, the curator speaks of “an unpredictable and growing work that cannot be controlled by transforming the metaphor of the artist, or the tireless creator, into something real: an alchemic agent who changes things unceasingly, an act of creation that continues forever.” A more eloquent negation of design as an activity is hard to find.

This exhibition does avoid the common over-reliance of other museum design shows on conventional product typologies such as furniture, posters, clothing or building models. Exceptions are Tomáš Libertíny’s 2006 Made by Bees honeycomb vase and Julijonas Urbonas’s 2016 When Accelerators Turn into Sweaters, an installation of copper filaments woven during his artistic residency at CERN’s Large Hadron Collider into… sweaters. It does include more prosaic products and tools, such as the 3D-printed, aluminum alloy Ozone Monitoring instrument, designed at ESA’s European Research and Technology Center (ESTEC), as well as prototypes for zero-gravity inhabitation products—a nail clipper, an ice-cream maker, a coffee maker—designed by students of the Integrated Product Design master’s degree program at Milan’s Politecnico University, under the ESA-supported Space4inspiraction research initiative.

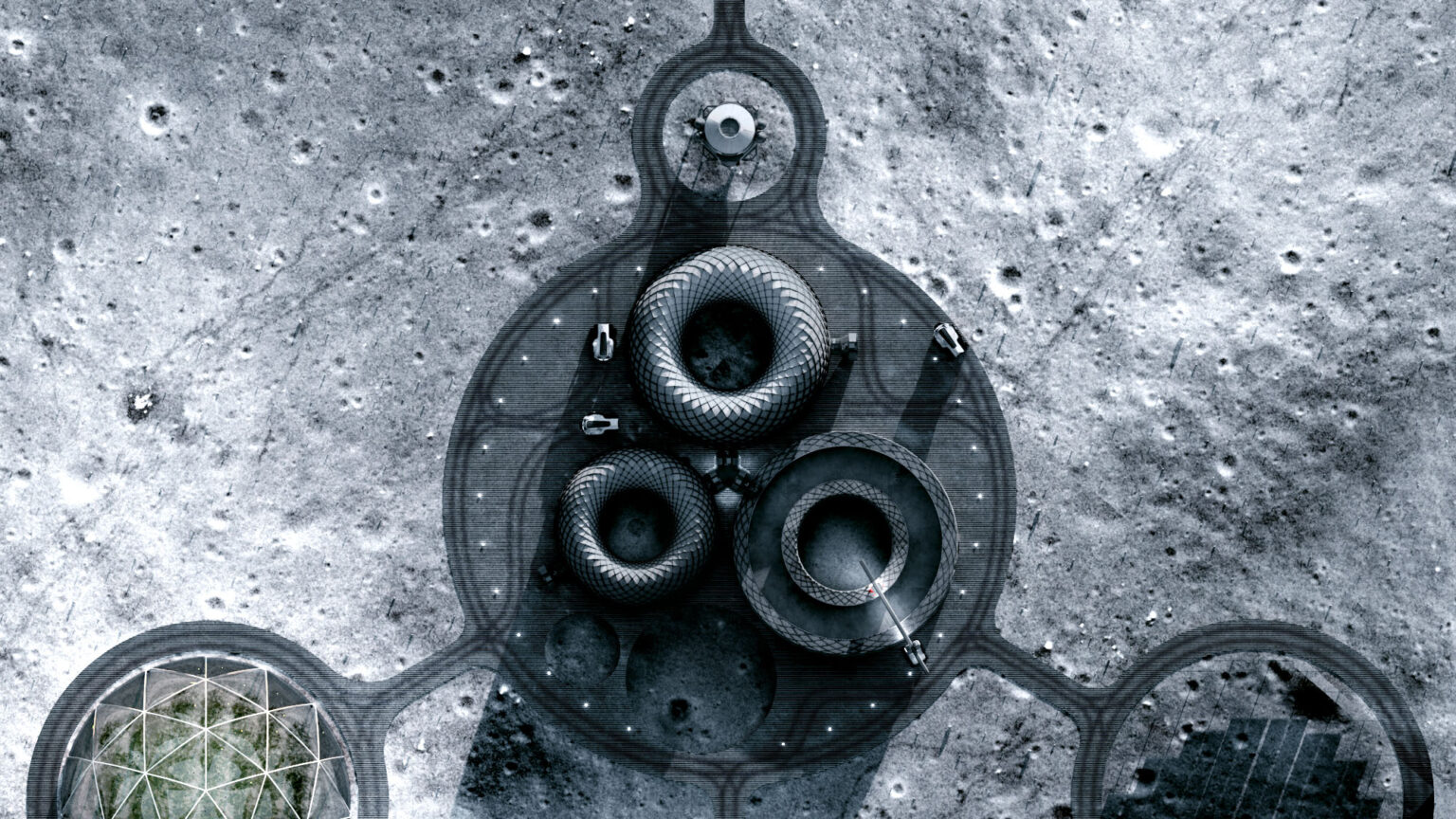

In their installation Planetary Personhood; A universal declaration of Martian rights, the Nonhuman Nonsensecollective employ derision, in a manner typical of critical and speculative design, to question the politics behind space exploration. They ask us how might humans to go to Mars “without the colonialism.” As designers, could they have gone further in probing and exposing the political agendas and socio-economical frameworks upon which extraterrestrial exploration depends? They could start with the agendas implicit in two other Triennale exhibits: Decalogue for Space Architecture, a ten-screen installation commissioned to the corporate architecture firm Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM), which speculates on human-centered design for an interplanetary future. And the 2020 Project Olympus, a design proposal for the first permanent settlement on the lunar surface by the Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG) and ICON, a 3D-printed home construction company. Are such agendas driven by private interests—from individual hubris to corporate greed—or by a conception of the public good grounded on collective goals? Such questions are conspicuously absent from a surprisingly apolitical exhibition.

Instead of showing works lacking design’s transformative potential or agency, the Milan Triennale could have celebrated a design culture where responsibility is valued over authorship. A culture grounded in meaningful design actions that reveal, interpret and discuss the unknowns we need to know. These include the ethical and epistemological consequences of artificial intelligence. How dark patterns shape fast fashion consumption and production. How fossil fuel corporations drive public discourse, policy and research over climate change. Or how social media algorithms lead citizens to vote into power—as Italians did during this Triennale—far-right parties or authoritarian leaders.

By questioning future scientific and technological agendas, but also past design intentions and solutions, design practitioners can and are critically addressing how our known and unknown worlds are built, unbuilt—and built otherwise. Design research grounded not on national competition, individual obsession or corporate profit, but on local communities and networks of transnational collaboration and solidarity, already exists. Showing how its results provide alternatives that empower citizens, strengthen civic infrastructure, defend democracy and expand our fragmented public sphere would suggest a confident, collective hold on the known and unknown is possible. 2025 is just around the corner.

—

My third review for Metropolis in 2022, written over the Summer following a visit to the Triennale in late July.