Market needs, industry trends and consumer anxiety have turned cow’s milk into an increasingly complex and often contentious foodstuff. Today we drink it in countless variations and declinations, which come with less fat, more nutrients, no lactose, new flavours, old promises and a longer life. Many, who find cow’s milk a harmful substance to the human body or its industry a hazard to the environment, get their milk from other mammals, grains and fruits. Regardless of what we call it or how we drink it, milk is, just like most consumer products, part of an elaborate and highly designed system connecting producers to consumers, which we interact with on a superficial level: the level of the interface.

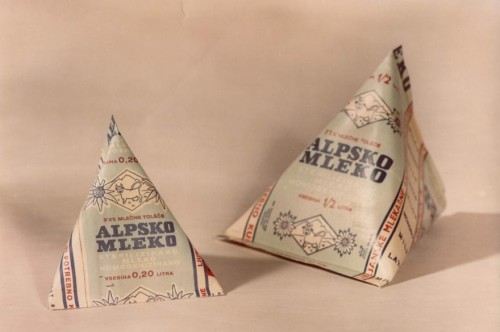

For this timeline installation we tried to gather as many examples of how cow’s milk has been preserved, packaged and presented since the first Ljubljana Design Biennial took place in 1964. For this we’d like to give special thanks to the dairy companies that provided us their current and older packaging items, and also the City Museum of Ljubljana. This overview of 50 years of packaging of a particular product in a specific market show how advances in technology, changes in legislation and choices in representation influence the design of these interfaces. Apart from trends in marketing, graphics or brand values, how do these designs express notions of nature, family, health, freshness, locality or even nationality – but above all, trust? Much like the product and the system, the milk business has become increasingly complex, competitive and global. Here’s an example. Founded in 1956 as a company of the Main Cooperative Union of Slovenia, Ljubljanske Mlekarne grew to become the most important dairy of Yugoslavia and of independent Slovenia after 1991. Its most known milk product, Alpsko Mleko, was introduced in 1967 as the first UHT (Ultra-High Temperature) milk in the country, where it became synonymous with UHT milk. Its first packaging design is centred around a cow, but from 1992 this symbol – curiously absent from virtually all packaging of the eight milk brands that make up today’s Slovenian highly diversified dairy market – was replaced by a national view of a transnational mountain range. In its latest iteration, lake Bled became less recognizable, but a “100% Slovenian milk” box was added. This happened shortly before the company was purchased in 2013 by the French conglomerate Lactalis, the world’s largest milk producer, through its Croatian subsidiary Dukat. That same year, another dairy, Mlekarna Vipava, was acquired by Ekolat, a Slovenian-Italian joint-venture now solely dedicated to producing Mozzarella cheese.

Mergers and acquisitions in the food industry, the end of EU milk quotas in 2015, milk price fluctuations and ever faster, shorter trends in food consumption are contributing to shifts in the flow of milk as a commodity. This is changing the way consumers trust, or often mistrust, corporations, brands and even the state, on national or transnational level. Especially when, as it happens with food – remember the 2013 horse meat scandal? – values such as safety, quality, origin and nationality are involved. Like the other BIO 50 Knowing Food group proposals, this timeline suggests that a food chain can be redesigned as a food network. One milk interface proves this is happening, successfully, in Slovenia. It’s called the Mlekomat.

The sale of raw or unpasteurised milk – once the only milk available – has for long been illegal or highly restricted in many countries, including the USA, Spain or Portugal (where we’re from). However, a few years ago vending machine systems started being implemented in countries such as Switzerland, Italy, South Korea and (since 2008) Slovenia, raising the debate over the benefits and risks of drinking raw milk and questioning/pushing the limits of technology and legislation around it.

Like any milk package, these interfaces connect producers with consumers with a simple promise: they provide raw milk, collected within 24 hours, in an unlabelled container (glass or PET bottles, or you can bring your own), with a fixed value (€0,10 per decilitre), safely (using sophisticated technology such as UV light for sterilization and GSM for remote monitoring), and conveniently (in markets, petrol stations and other public places).

Each Mlekomat is attributed to a local farmer, which cuts out middle men and provides a better value for the farmer’s milk. This direct connection also redefines the very notion of producer-consumer trust: users can simply call the person whose name is on the machine’s front.

Milk packaging designs range from generic-looking Tetra Pak® bricks to glass bottles heavy with regional imagery, aimed at creating and sustaining trust between producer – but also brand owner, share holders, distributors… – and consumer. On these machines however, graphics are generally amateurish, often including a clumsily drawn cow. On and beyond the surface, what then is the best, or more appropriately designed interface? You be the judge.

Design shapes how we perceive and experience food as a product of daily consumption. All the interfaces on this table are thus shaping, but also responding to the ways Slovenians eat and drink in the twenty-first century. Does this mean that when designed right, milk can still be raw, whole, local and good for you? Think about how a milk interface, including a Mlekomat machine, is designed the next time you use it. The nearest one is only a 10-minute walk (or a bus stop) away, here in Fužine. Express your opinions with the hashtags #mlekomat #knowingfood #bio50

—

This essay is published on the website of BIO 50, the 24th edition of the Ljubljana Design Biennial, in which I took part in the Knowing Food group with Pedro and Rita as Fabrico Próprio.

Comments are closed.