The Trump World Tower possesses all the virtues and vices of the buildings that made New York the greatest metropolis of the twentieth century. Like many of the city’s great skyscrapers—such as the Woolworth or the Chrysler building—it’s more than a feat of the architect; it’s a flamboyant statement of the wealth, power and greed of its owners.

Soaring 881 feet, Donald Trump’s ambitious housing enterprise stands close to the East River on Manhattan’s Upper East Side. Seen from afar, the tall and sleek tower designed by Costas Kondylis and completed in 2001 rises from the ground as the residential version of Stanley Kubrick’s black obelisk. Its seamless curtain-wall of bronze-colored, highly polished glass wraps the building’s seventy-two floors, reflecting its surroundings while revealing glimpses of its almost 400 apartment units.

Thanks to extensive air rights purchases and negotiations, the tower imposes a strong presence on the skyline while making a light mark on the ground. Flanked by public areas, fountains and trees on both sides of its First Avenue entrance—East 46th Street to the north, East 47th street to the south, opening up to the Dag Hammarskjöld park—it has a much smaller impact on this section of the United Nations Plaza than its predecessor, The United Engineering Center.

In 1961, Shreve, Lamb & Harmon designed and completed the U.E.C., an unremarkable office building that doesn’t even demand a description: it looks just like many other, built—around Manhattan and around the world—in the modern idiom of concrete, glass and steel. Demolished in 1997, it has since hardly been missed.

Unlike Trump’s tower, it occupied the entire end of the block, providing little public space to this section of the United Nations Plaza. Trump’s street-level generosity wasn’t enough for residents of the neighboring buildings, who at the time campaigned to stop him from putting up the world’s tallest residential tower. Their problem was not the street, but the views: instead of the squat twenty-two floors of the U.E.C., Upper East Siders such as Walter Cronkite—resident of the 870 United Nations Plaza twin towers across the road—would get a much thinner, but much taller obstacle blocking their views of the Chrysler building.

Trump being Trump, he found a way to have his tower built—his way. He is the kind of man who built the New York City we love and loathe; the city of ruthless, powerful businessmen and their structures of collective fame and personal scandal. This tower is perhaps the last remaining example of an era when buildings could still be politically incorrect edifices of ego, as Trump is one of the last big egos in town.

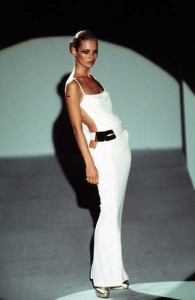

Unlike the first modern slab, curtain wall clad building in the city—the United Nations Secretariat across the Plaza—and the naïve international-style iteration it replaced, there is no quest for human or architectural progress here. But again, none of that was ever part of the quest for New York’s greatness. This tower is as modern, minimal and utopian as a Tom Ford 1996 Gucci evening gown, down to the brass doorframes. It’s another tall, sexy model on Manhattan’s urban catwalk.

With apartments costing up to $14 million, we can think of the tower’s own snug-fitting, slightly sheer dress as that same Gucci gown, worn by some oil oligarch’s trophy wife as she leaves the garage in an armored limousine. But unlike the Seagram Building—the original and first of many other of New York’s “black slabs with optional plaza” — modern ethos and sophistication are only skin deep here. This is no architectural landmark: it’s real estate. It’s not supposed to inspire the intellect; it’s supposed to sell. And we all know purchasing power is not often held by those of modernist restraint: from the lobby’s Murano chandeliers and Bergère chairs to the $50 cocktails at the World Bar, the tower’s sleek, alluring outside clashes with its brash, repulsive inside. In the end, this building, just like New York, shows us that good taste cannot be mandated. Much like its owner, certainly some of its residents and most of this city, the Trump World Tower is more money than art, more drama than reason, more mafia than Mies. And that’s why it belongs here.

__

This article was the second assignment for Justin Davidson‘s part of the Criticism Lab course. Held as a professional writing workshop, Davidson’s class focused on “journalistic criticism [as] a more collaborative effort than a one-name byline implies”. Therefore, students reproduced the process by which a piece of writing gets into print by editing each other. We were divided up into groups of three, and each member wrote one story, edit a second and fact-check/copy-edit a third, in round-robin fashion. This was a great learning experience, and I had great late-night fun with co-“team late” members Laura Forde and Jim Wegener.

On this assignment, we were asked to choose one of the 54 before-and-after pairs of images in the photo gallery of Justin Davidson’s “The Glass Stampede” article and write 400-600 words specifically addressing the question of whether the new structure on that site is an improvement over the old. We should ask: What does the change do for the block? For the neighborhood? How well does the new structure fit into and interpret its location on a New York City block? We needed not limit ourselves to the buildings that accompanied our articles; we may have chosen any new construction, so long as we could document what was there before and compare new to old. We should have discussed our choice with our editor before we wrote. Jim was the editor and Laura was copy editor of this piece.

Comments are closed.