While delving through the turbulent history of Brooklyn Bridge Park, I found inspiration in the words of Frederick Law Olmsted, the godfather of park building in America: “There is one large American town, in which it may happen that a man of any class shall say to his wife, when he is going out in the morning: ‘My dear, when the children come home from school, put some bread and butter and salad in a basket, and go to the spring under the chestnut-tree where we found the Johnsons last week. I will join you there as soon as I can get away from the office. We will walk to the dairy-man’s cottage and get some tea, and some fresh milk for the children, and take our supper by the brook-side;’ and this shall be no joke, but the most refreshing earnest.”. When Olmsted pronounced these words in 1870, he was referring to the “large town” of Brooklyn and its soon-to-be-finished park of his design.

Today, Brooklyn is a borough of New York and Prospect Park the city’s second biggest green playground. Much has changed in our lives, our societies and our cities, but what is the ongoing controversy behind Brooklyn’s newest park-to-be but a sign that we have forgotten Olmstedt’s lessons? Since when did urban living stop being simple?

The citizens of post-industrial Brooklyn have for decades attempted to recover the section of their shoreline that stretches from under the bridges down to Atlantic Avenue. After the end of cargo operations, in 1984 the Port Authority announced plans to sell its man-made, projecting piers for the commercial development of four 15-story housing units on the site. Community and advocacy groups – such as the Brooklyn Heights Association and The Brooklyn Bridge Park Coalition – began to make noise, discussing and ultimately influencing the overwhelming rejection of this proposal by community boards, local and city-wide civic associations.

Later, a 13 Guiding Principles chart, setting the development goals for this park, was signed in 1992 by local elected officials. It coincided with the creation of a Local Development Corporation (LDC), which initiated design and discussion of the park’s initial master plan. In 1995, the “no-housing” Schnandelbach Plan was the first vision for the park to be revised and approved by the community. It would inspire and inform the 2000 Vision Plan that led to a Memorandum of Understanding signed in 2002 between State and the City. Both committed to $150 million in funds to build Brooklyn Bridge Park, while mandating the park to be, when built, economically self-sufficient in terms of maintenance and operation costs. This meant the annual operation and maintenance budget should result in revenue generated from and within the park.

If all would have gone as promised and planned, the park now in construction (Phase 1 started last October) would be built according to this plan. It reflected 20 years of discussion and resident input and was already “a park that paid for itself”: based on a self-sustaining concept, normal park maintenance costs (lawn mowing, etc.) would be supported by commercial revenues generated on-site. Its capital costs – including eventual refurbishment and periodic re-investment in infrastructure – were to be covered by public capital budgets. A working marina, active recreation uses (such as a pool, ice-skating rink and indoor playing fields) and a variety of restaurants and catering facilities would generate long-term jobs in the hospitality industry and marine trades. These programmatic elements were planned as balanced, limited, water-enhanced, park-oriented commercial uses to support a maintenance budget based on NYC Park Department figures of the time.

But sometime between May of 2003 and December of 2004 the tide secretly changed on the Brooklyn waterfront. The current plan, now being put in place by the Brooklyn Bridge Park Development Corporation (subsidiary of the Empire State Development Corporation) and managed by the Brooklyn Bridge Park Conservancy, threw away all that discussion and planning, severely increased the Park’s estimated maintenance and operation costs, and to many of its opponents created an artificial, unnecessary complexity in terms of landscape design and programmatic use.

Olmstedt’s simple pleasures of dinner by the stream are not enough for today’s over-caffeinated, fitness-obsessed, hyperactive New Yorkers: according to the park’s development corporation plan and Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates’ design, Brooklyn Bridge Park and its 6 piers will be a cross between Coney Island, a suburban backyard and a treadmill room. Artificial beaches and water access ramps, a calm water area for “human-powered water craft”, slips for the mooring of historic vessels, a marina for sailboats and powerboats, a “picnic peninsula”, several children playgrounds and dog runs, a nature preserve, three multipurpose fields (each as the size of a soccer field), six basketball courts, two tennis courts, three sand volleyball courts, an in-line skating rink, bocce courts and 10 handball courts. Phew.

Both the park’s and the conservancy’s literature, presentations and websites – while boasting the views, activities and amenities of the park – fail to describe, and are even defensive about, the residential development program that will allegedly make all this possible. It may not seem like it in the renderings and artists impressions of the park’s bright, green future – it is also naturally fun-packed with sustainable features – but the park will be “little more than a passive recreational park of narrow piers and parkways dominated by luxury housing” – says Ethan Kent of Project for Public Spaces, a nonprofit organization dedicated to creating and sustaining community-building public places. Even if accounting for just over 10% of the park’s total 85.2 acres it is, also according to Kent, a perverse addition to the plan: “Instead of housing, which is the most private of all forms of development and largely incompatible with great waterfronts and public park interiors and entranceways, these areas should be the site of buildings that generate revenue while serving a public purpose, like Brooklyn-based cultural institutions, food establishments, arts organizations and non-profits”. This will also be the first time in the city and the state of New York that housing is actually built as part of a public park. So instead of a well-integrated, organically evolving waterfront, Brooklyn may end up with a new Battery Park City (coincidentally, its recent Teardrop Park was also designed by Van Valkenburgh).

The long-running controversy over the planning, discussing, funding and ultimately building of Brooklyn Bridge Park began as a promising, participatory process that was a direct heir to Jane Jacobs’ legendary defiance of Robert Moses, and an exemplary way of “making city” based on the delicate balance of public and private interests. But somewhere along the way, things got complicated, priorities and necessities changed, and that balance was put at risk. Today, this park can be seen as a tug of war between necessity and folly, urban public space and private privilege. What came first? The need for complexity or the demand for development?

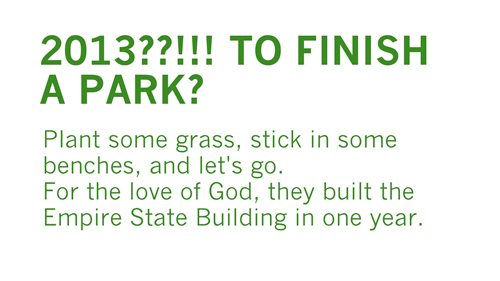

The first phase of construction started at the beginning of very uncertain times. Suddenly, the value of property and even the value of money are sinking before our eyes. As I stand under the Brooklyn Bridge before the murky waters of the East River, I can only hope that in 2013, when two-thirds of the park are supposed to be built, we won’t have to look back to Olmstedt’s words in sorrow and regret. For then, as now, “The park should, as far as possible, complement the town. Openness is the one thing you cannot get in buildings. Let your buildings be as picturesque as your artists make them. This is the beauty of the town. Consequently, the beauty of the park should be the other. It should be the beauty of the fields, the meadow, the prairie, of the green pastures, of the still water.” If only building a park would be this easy.

__

This text was written in December of 2008 – when the photos that illustrate it were also taken – for Karrie Jacobs‘ Urban Curation course. For this final project, each student selected a topic from a list of the city’s many ongoing controversies, from the redevelopment of Coney Island to a proposed high rise on Madison Avenue to the rezoning of the Lower East Side. Students were required to research the controversy and write an argument for or against the proposed change. I chose the on-going controversy behind the Brooklyn Bridge Park.

Comments are closed.